por Amanda Arrigo

In 2020, child migrants (aged 19 or under) accounted for 14,6% of the total migrant population and 1,6% of all children (MIGRATION DATA PORTAL, 2021). Unfortunately, between 2014 to 2020 at least 2,300 children died or went missing during their migration journey (IOM, 2020 apud MIGRATION DATA PORTAL, 2021). It is needless to point out that child migration is a phenomenon that is happening and has become a recognized part of today’s migration flows globally. Nonetheless, in research and policy debates it is considered a new area of concern and more than often children are portrayed as being passive victims of exploitation and not human beings that can be actively involved in decision-making regarding their own present and future (IOM, 2011). In addition, in literature they are frequently seen as an “appendix” of their family through the migratory process (MARTINELLI, 2017).

This analysis will focus on a specific group in child migration: unaccompanied migrant children. By definition, these children are people aged 18 or under, as written in the article 1 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989, who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so (OHCHR). In 2021 only, more than 112 000 unaccompanied children arrived in the United States of America (CONGRESSIONAL, 2021) looking for a better life but ended up being detained by the US government.

Who are the unaccompanied children that migrate to the USA?

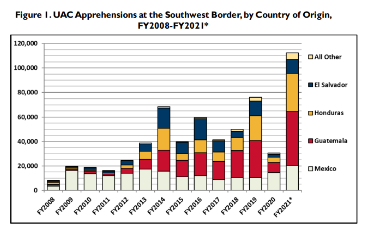

These children are mostly from the Northern Triangle countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras) and are apprehended along the southwestern border with Mexico. The reasons behind these children’s motivation for going on this very dangerous journey are multi-faceted (CONGRESSIONAL, 2021). According to research made by the Congressional Research Service of the United States in 2014, the following push factors were identified: crime, economic conditions, poverty, and the presence of violent transnational gangs in migrants’ countries of origin.

Sources: FY2008-FY2013: United States Border Patrol, “Juvenile and Adult Apprehensions- Fiscal Year 2013”. FY2017-FY2018: Customs and Border Protection, “U.S Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions

When the data is analyzed, it is clear why these children decide to leave their home: the homicide rate of Guatemala is 21.6, El Salvador is 36 and Honduras is 44.23 (per 100 000 inhabitants) (INSIGHT CRIME, 2022). Moreover, some of other factors are lack of employment opportunity and stability, lack of security conditions, corruption and weak governance, climate change, natural disasters and food insecurity (CONGRESSIONAL, 2021).

Therefore, it is clear that these unaccompanied children who have been migrating to the USA are not doing it out of fun: more often than it should, they see that going on this journey and trying to live in the USA is their only hope to escape the violence they are suffering at home.

Once they get to the USA, what happens?

They are placed into a “network of shelters” that are run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement. According to the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, these shelter care providers “offer temporary homes and services, including educational, medical, and mental health services and case management to reunite children with their families” (RELIEF WEB, 2021). At least that is what is in the paper. The reality is very different.

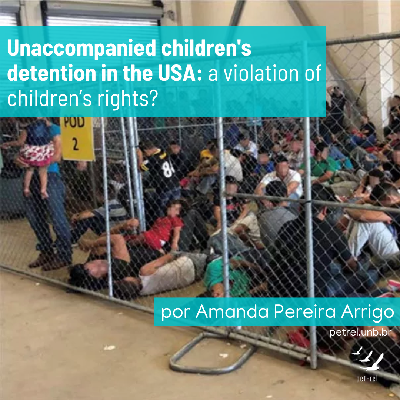

Journalists and even the staff of these shelters have been risking themselves trying to show publicly the real conditions of children’s detention in the United States like Human Rights Watch denounced, in 2018, in its article: “In the freezer: abusive conditions for women and children in US Immigration Holding Cells” (HRW, 2018). What they are bringing into light is the fact that migrants are kept in cells so cold that they have a nickname for them: “hieleras”, which means “freezers” in Spanish.

According to the above mentioned report, women and children who are detained along the border are taken to these cells where they usually stay one to three nights. They sleep on the floor, frequently with only a Mylar blanket (similar to foil wrappers) and often border agents require them to remove sweaters and clothing items for “security reasons”, before entering the cells. Human Rights Watch (2018) interviewed 110 children and women detained with their children and the answers were preposterous. They said that they were not allowed to shower, sometimes for days, until just before their transfer to long-term facilities and they did not receive any soap, toothbrushes or other hygiene items. As expected and despite migrants constantly reporting these conditions, the US Customs and Border Protection officials deny that these cells are cold (HRW, 2018).

In addition, US immigration authorities place adult men, teenage boys and girls, and mothers and younger children in different cells, which means that families are often separated (HRW, 2018). Family separation and detention have serious consequences for the mental health of migrants who, on top of all, are already experiencing traumatic events throughout their journey.

Moreover, according to an article published in the news channel CNN in 2019, often older children feel the responsibility to take care of the unaccompanied younger ones, since there is no one around to look after them. The journalists describe the situation they found in the US Border Detention Center for children as unacceptable for many reasons: children were kept in these “jail-like” border facilities for weeks, without being authorized any contact with their family; they did not have access to shower and toiletries; many were sick and were not getting medical help; children as young as 2 or 3 were separated from adult caretakers and needed to rely on the care of older children; and the food provided in the detention centers was extremely unhealthy: instant oatmeal, instant soup and previously-frozen burrito (CNN, 2019).

One could argue that these reports are old and only happened under the Trump administration. Unfortunately, the same conditions are reported nowadays, in 2022, under the Joe Biden government. The news website Politico, in partnership with The Marshall Project (a project covering the US criminal justice system) reported in June of 2022 similar conditions as in 2018 and 2019: detention in freezing facilities and sleepless nights on cement floor under the glare of white lights (FLAGG & PRESTON, 2022). This article also shows that out of nearly 2 million people detained by the US Border Patrol from February 2017 to June 2021, more than 650,000 were children and one third of them were held in the cells for more than 72 hours, the maximum amount of time permitted by the US legislation (FLAGG & PRESTON, 2022).

Even the USA’s highest immigration official, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, acknowledged publicly that “A Border Patrol facility is no place for a child”. With all of this information stated, it is important to understand two concepts that are present in the way the US government deals with unaccompanied migrant children: euphemisms (CERNARDAS, 2016) and deportability (DE GENOVA, 2020).

The use of euphemisms in children’s detention in the USA

Initially, when people hear the discourses that the US government places unaccompanied children into a network of shelters, they are led to believe that the government truly takes care of these children. What the section above showed, however, is that “shelter” is the least suitable word to characterize the detention centers children are held in. According to Pablo Cernardas, a well-known researcher in this matter, euphemisms are used in the political sphere to “camuflate”, describe something in a different way by occulting or desvirtuating all or part of the reality” (CERNARDAS, 2016). By doing that, they manipulate the way the public reacts, which could be very different if they knew the reality behind these euphemisms.

Moreover, when the border control practices (such as requiring migrants to take off their sweaters), technology and constant vigilance are added up to the equation, it is clear that the US migration policy is securitized. This means that unaccompanied migrant children are seen as a threat to the US society and they only have their rights recognized when their status becomes regular- until that, they are referred to as “illegal migrants”, as if they have committed a crime for trying to change their life for the better (MARMORA, 2010).

With that said, it is likely that the way the US government treats migrant children in their territory is not right and cannot be overlooked. For this reason, the following session will make an effort to enumerate all the violations that the United States of America is committing when it comes to unaccompanied migrant children in their country.

Children’s rights violation: Which norms and principles of international law is the USA violating?

Before answering this question it is important to address the matter of asylum for children. In the case of unaccompanied children who leave their country of origin due to the fear of being obliged to join a violent gang, for example, there should be no question whether their refugee’s status can be recognized or not. According to the 1951 Convention on the matter, a refugee is “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion” (UNHCR). What many states seem to “forget” is that children can be persecuted only for being children.

Considering that, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2018) put forth guidelines regarding international protection for migrant children. They highlight some reasons why children, in specific, can feel the well-founded fear of persecution: a) threat to life or freedom as well as serious damages in relation to age, opinions, feelings and psychological structure of the solicitant; b) discrimination that can lead to substantial negative impacts on children; c) recruitment of children; d) child trafficking; e) female genital mutilation; f) domestic violence; g) forced marriage; h) child labor; i) forced prostitution. As it can be seen, there are many forms of persecution of children and they need to be taken into account by the US government- and governments worldwide.

In order to specify the general principles of the Convention on the Rights of Children that need to be implemented by the States in this matter, the Committee on the Rights of Children identified four of them as being essential: 1) States parties must respect and ensure the rights specified in the Convention without any kind of discrimination (Article 2); 2) the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration in all instances (Article 3); 3) recognition that every child has the inherent right of life and the States must guarantee their development and survival to the maximum extension possible (Article 6); 4) States shall assure that every child can express their views freely in all matters affecting the themselves (Article 12).

As it was stated above, the rights of Children are clearly nominated in the Convention on the Rights of Children, the most ratified international instrument: 196 countries are members (UNICEF). However, the only country which has not ratified this Convention is the United States of America. Although it is an instrument of soft law, it is important for children everywhere and the mere fact that the USA has not ratified this document shows how unwilling they are to take care of children. Nevertheless, since it is almost an universal instrument, it is necessary to take into consideration the violation of these rights by the US government in this matter.

Specifically regarding unaccompanied migrant children, when the Border Patrol constantly leaves the white lights on, even during the night, yells orders and does not offer any kind of comfort, as it was shown before, they are violating children’s right for protection against all forms of violence, physical and mental (article 19 of the Convention on the Rights of Child 1989). When the first thing the US Border Patrol does when they see an unaccompanied migrant child is detain them, they are violating their right to only be detained if it is a last resource measure (article 37).

In addition, when children are not given the opportunity to get in contact with their family during their time in the detention facilities, it is a violation of the 9th Article. Article 22 is violated when asylum seeker children are left in such poor conditions as shown in the beginning of this article. Moreover, when sick children receive no medical care inside the detention centers, it is a violation of Article 24. When the detention facilities are so horrible that children are actually afraid of being there, it is a clear violation of article 27 that states the “right of every child to a standard of living adequate for the child's physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development”. The list goes on.

Final Considerations

In summary, what this article meant to show are the conditions under which unaccompanied children are being submitted to in the USA in their attempt to create a better life for them. Even though their rights are clear in the Convention, they are being violated everyday for years now and this situation does not seem to be changing. It is necessary that people from all around the world join efforts to help. First, turning public what was described in this article and second, to end these practices. Scholars can contribute by researching about Migration and Refugees and bringing into light these themes that are not mainstream in IR even though their relevance is clear.

References

CERNADAS, Pablo Ceriani. A linguagem como instrumento de política migratória: novas críticas sobre o conceito de “migrante econômico” e seu impacto na violação de direitos. Sur, Sao Paulo, vol. 13, nº 23, 2016, p. 97- 112.

CNN. We went to a border detention center for children -What we saw was awful, 2019. Available at:We went to a border detention center for children. What we saw was awful (opinion) | CNN. Access on 14 September 2022.

CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE. Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview, 2021. Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R43599. Access on 16 September 2022.

DE GENOVA, Nicholas. O poder da deportação. Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana – REMHU, Brasilia, vol. 28, n. 59, ago. 2020, p. 151-160.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH. In the Freezer: abusive conditions for women and children in US Immigration Holding Cells, 2018. Available at: In the Freezer : Abusive Conditions for Women and Children in US Immigration Holding Cells | HRW. Access on 16 September 2022.

INSIGHT CRIME. Border Crime: The Northern Triangle and the Tri-Border Area. Available at: https://insightcrime.org/indepth/nt-tba/mapping/. Access on 14 September 2022.

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION. Unaccompanied Children on the Move. Available at: Unaccompanied Children on the Move. Access on 15 September 2022.

MÁRMORA, Lelio. Las politicas de gobernabilidad migratória. Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana – REMHU, Brasilia, ano XVIII, n. 35, jul./dez. 2010, p. 71-92

MARTINELLI, Patrícia Nabuco. Unaccompanied children in Latin America: initial

reflections on the situation in Central America. Revista Interdisciplinar de Direitos Humanos. Bauru, v. 5, n. 1, p. 77-96, jan./ jun., 2017

MIGRATION DATA PORTAL. Child and Young migrants, 2021. Available at: Child and young migrants. Access on 16 September 2022.

POLITICO. ‘No Place for a Child’: 1 in 3 Migrants Held in Border Patrol Facilities Is a Minor, 2022. Available at:‘No Place for a Child’: 1 in 3 Migrants Held in Border Patrol Facilities Is a Minor - POLITICO. Access on 15 September 2022.

RELIEF WEB. USCRI Factsheet: Arriving Unaccompanied Children, 2021. Available at: USCRI Factsheet: Arriving Unaccompanied Children, July 2021 - United States of America | ReliefWeb. Access on 18 September 2022.

UNICEF. Convenção sobre os direitos das crianças. Available at: Convenção sobre os Direitos da Criança. Access on 19 September 2022.

UN HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE. Convention on the Rights of Child. Available at: Convention on the Rights of the Child | OHCHR. Access on 14 September 2022.

UN REFUGEE AGENCY. What is a refugee? Available at: UNHCR - What is a refugee?. Access on 17 September 2022