Ana Luísa Vitali

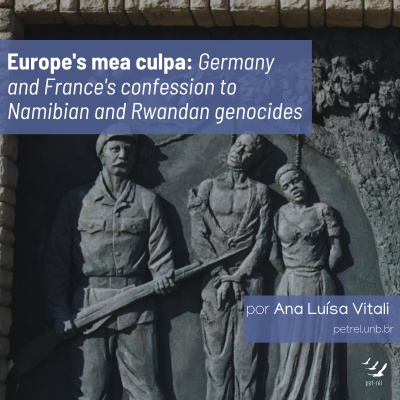

Europe's presence in Africa has been ongoing for centuries. In the 15th century, during the Age of Discovery, a few African countries were reached by Portuguese explorers, but the expedictions remained very restrained until the 16th and 17th centuries. At that time, the Berlin Conference in 1885 started a period known as Scramble for Africa, when Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and others divided African nations between themselves and began colonisation. As claimed by Bismark, who initiated the Conference, this would avoid violent engagements in Europe. As it is known now, that was not the case: World War I followed a few decades later, and the outcomes of this colonisation led to massacres of almost 1 billion people, only considering the Namibian Genocide (1904-1908) and the Rwandan Genocide (1994).

Namibia was a British colony until 1884 when the German Empire established rule over the territory. That lasted until 1915 when South Africa began controlling the country, which then became independent in 1990. The genocide took place during the German colonisation between 1904 and 1908, and the victims were Herero, Nama, and San peoples, who were rebelling against the colonisers. According to estimations, the Germans killed 100,000 people, and survivors — essentially women and children — were sent to concentration camps, where they were enslaved and used for medical experiments and research (CONRAD, 2008, p. 129). After the installations were closed, the small group of survivors were forced to wear a metal disc with a registration number and they could not own land or cattle, another death sentence (SCHALLER, 2008, p. 296).

Whereas Namibia is named the forgotten genocide, Rwanda's massacre is better known, as reports show that over 800,000 Tutsi died in just 100 days. Although this conflict was between Hutus and Tutsis — both Rwandan —, it all occurred due to colonisation, as shown by Patriota (2010, p. 108). These two groups were not friendly, yet they were not violent. When the Germans and Belgians promoted Tutsi supremacy, even by having documents to separate the said races, endless cycles of violence began. Other countries, such as France, also had a role in the genocide even though they did not participate in the colonisation. In 1994, the French held Operation Turquoise, which sided with the Hutu perpetrators, and was slow to react once the killings started. Furthermore, this inaction was responsible for many deaths.

Germany's apology and monetary restitution

After more than a century since the events, Germany issued last May an apology for the Namibian genocide, officially recognising its fault. This came after over five years of negotiations since the Germans also intended to give monetary restitution besides the confession. Thus, both countries have agreed on a number: 1.3 billion dollars for infrastructure, healthcare and training projects in the affected communities, paid over 30 years (ISILOW, 2021). However, the question remains: is money enough to account for mass killings and property seizures that destroyed generations?

In this regard, the descendants of the victims are mostly rejecting the deal, stating that the negotiations did not include them and called the agreement a 'sell out', but Foreign Minister Heiko Maas denies, affirming the groups have participated (BUSARI, 2021). The main complaint from the Herero and Nama heirs is about their land, as German Namibians are believed to be the biggest group among the white farmers — they own about 70% of the country's farmland, even though they only make nearly 1% of the population. The affected wish not only for the projects but also that Germany buys back ancestral land, since those were taken during the genocide (GERMANY…, 2021).

The issue seems to be the German's motivation for the apology. For example, Namibia had pushed for describing the investments as reparations, yet Germany rejected the term, which would have amounted to acknowledging guilt under the 1948 United Nations Convention on Genocide. Nevertheless, reparations could have also made Germany — and other former European colonial powers — liable to claims from other former colonies (EDDY; NORIMITS, 2021). Therefore, the Germans seem to want to put this matter to rest by admitting some guilt, but not generating too much publicity around it — hence the rushed payment with no direct communication with the victims.

France's admission of guilt and redeemed relations

In another historic declaration, a couple of months after the release of a report on the subject, French President Emmanuel Macron has admitted that France had a "serious and overwhelming" role in the Rwandan genocide, as French officials armed, advised, trained, equipped, and protected the Rwandan government. During his speech in Kigali, he stated that there was a political responsibility but focused on survivors and did not explicitly ask for forgiveness, instead just took accountability for past actions. Yet, this was the only deed: a speech with a few promises. While it was enough for a few people and received favorably across Rwandan media (BARIYO, 2021), it raises the question of if Macron believes this was sufficient and this matter is resolved for good, as France made its peace with it.

One promise made was regarding Hutu perpetrators that live in France. There have been a considerable number of those who fled Rwanda and live comfortably in Europe away from justice (UWIRINGIYIMANA, 2021). In 2020, one significant person was arrested, boosting bilateral relations: Félicien Kabuga, who allegedly financed the genocide. The International Criminal Court tried to prosecute him at the genocide tribunal, but he was never found until last year. Although this was a significant development, many not as high-profile people still haven't been located, and this might be Macron's promise breaking point, as the judicial and legislative processes surrounding this matter are more complicated.

France is slowly attaining their goal of redeeming relations with African countries, as this speech was enough for Rwanda's two-decade leader, Paul Kagame. Still, will France turn a blind eye once again to modern-day violations? One of Kagame's plans is to hunt down and kill perpetrators exiled abroad instead of letting them have their trials — which is not being well-seen in Western capitals (DIZOLELE, 2021). Macron might be committing the same mistakes again, as he values political influence over human rights, the same as France did during the genocide. Still, people are angry due to this apparent support of brutal regimes in the name of false stability that does not reach the population, only its ruler (BELL; WOJAZER, 2021).

Final considerations

Is it ever possible to make up for destroying an entire country and its future generations? Even if it is not, what is the best way to mitigate those effects in the community? Nevertheless, Europe appears to be trying to correct its colonial history, but it's only scratching the surface. In Namibia today, monuments and cemeteries celebrating dead German soldiers, including the Schutztruppe, still outnumber those honoring the Herero and Nama victims of genocide (EDDY, NORIMITSU, 2021). On the other hand, France still has a robust military presence in Africa, as seen by Operation Barkhane in the Sahel, even though their mobilisation — officially justified by the fight against terrorism — is contested in several countries, where residents have repeatedly demonstrated against the French presence (AZZOUZ, 2020).

Even after the considerations made by Germany and France, two unmatchable colonial superpowers, this discussion is far from over. For instance, Tanzania — another previous German colony — is demanding reparations (WHEWELL, 2021), and potentially there's no end to where other African or maybe Asian and American nations could go in this movement. That said, the fact that European countries should be doing more is an understatement, but will they? And if they merely stop short at apologies, will other nations or International Organisations get involved, or will the matter be left alone? It definitely should not, but between corrupt African leaders and Europe's political agenda, there's no way of knowing it yet.

References

AZZOUZ, Fawzia. French military presence in Africa's Sahel a fiasco? AA, 7 September 2020. Available in: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/french-military-presence-in-africas-sahel-a-fiasco/1965919.

BARIYO, Nicholas. Macron Acknowledges France’s ‘Terrible Responsibility’ for Rwandan Genocide. Wall Street Journal, 27 May 2021. Available in: https://www.wsj.com/articles/macron-acknowledges-frances-terrible-responsibility-for-rwandan-genocide-11622132711

BELL, M; WOJAZER, B. Macron seeks forgiveness for France's role in Rwanda genocide, but stops short of apology. CNN, 27 May 2021. Available in: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/05/27/africa/rwanda-france-genocide-macron-forgiveness-intl/index.html

BUSARI, Stephanie et al. Germany will pay Namibia $1.3bn as it formally recognizes colonial-era genocide. CNN, 28 May 2021. Available in: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/05/28/africa/germany-recognizes-colonial-genocide-namibia-intl/index.html

CONRAD, Sebastian. German Colonialism: A Short History. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

DIZOLELE, Mvemba. The dark side of Rwanda's rebirth. Foreign Policy, 29 May 2021. Available in: https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/05/29/the-dark-side-of-rwandas-rebirth/.

EDDY, M; NORIMITSU, O. A Forgotten Genocide: What Germany Did in Namibia, and What It’s Saying Now. The New York Times, 28 May 2021. Available in: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/world/europe/germany-namibia-genocide.html

GERMANY officially recognises colonial-era Namibia genocide, BBC, 28 May 2021. Available in: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-57279008.

ISILOW, Hassan. Mixed reactions in Africa as Germany formally recognizes 'genocide' in Namibia. AA, 28 May 2021. Available in: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/mixed-reactions-in-africa-as-germany-formally-recognizes-genocide-in-namibia/2257660

PATRIOTA, Antônio. O Conselho de Segurança após a Guerra do Golfo: A Articulação de um novo Paradigma de Segurança Coletiva. Brasília: FUNAG, 2010.

SCHALLER, Dominik. From Conquest to Genocide: Colonial Rule in German Southwest Africa and German East Africa. New York: Berghahn Books, 2008.

UWIRINGIYIMANA, Clement. France's Macron seeks forgiveness over Rwanda genocide. Reuters, 27 May 2021. Available in: https://www.reuters.com/world/frances-macron-rwanda-reset-ties-survivors-expect-apology-2021-05-26/

WHEWELL, Tim. Germany and Namibia: What's the right price to pay for genocide? BBC, 1 April 2021. Available in: https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-56583994.