by Henrique Motta

COVID-19 has affected the world in a myriad of ways. Many lost their lives, and the impact of restriction measures on the economy and on people’s lives was immense. However, its political consequences are also a force to be reckoned with. Various governments have struggled to manage the pandemic, thus losing electoral force. Furthermore, the opposition to restriction measures has created political unrest all over the world. While the impacts on politics due to COVID-19 vary from place to place and its long term effects are yet to unravel, it is a much-needed effort for analysts to use comparative methods to analyze specific examples in order to better understand political dangers brought by the pandemic. The main goal of this piece is to analyze the recent developments in the Republic of Mali, where the spread of COVID-19 has catalyzed a coup d’état in August. Understanding what happened in this landlocked West-African republic can be a valuable exercise to comprehend the instabilities other developing countries, specially in Africa, may face throughout the pandemic.

Agitation in Mali had been seething since 2018. President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, often referred to in the media by his initials IBK, had won re-election in a controversial poll. Opposition parties claimed the elections were blemished by irregularities (AL JAZEERA, 2020e). At the same time, the Mali War, ongoing since 2012, ravaged the northern regions of the country. In the conflict, several insurgent forces are fighting a campaign against the Malian Government for the independence of northern Mali, which they named Azawad. The rebels seek to create an independent state for the Tuareg people counting on the support of major terrorist organizations, such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State. According to the Human Rights Watch (2017), during the war, Malian forces have perpetrated several human rights violations by committing extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, and arbitrary arrests, mostly against civilians. These factors had been sowing unrest in the country before 2020 and were determinant to the subsequent coup.

In the months preceding the pandemic, the country was preparing for Parliamentary Elections, which had been postponed several times. Surrounded by controversy, the polls were finally held on March 29. The opposition leader, Soumaïla Cissè was kidnapped three days before the voting took place, polling stations were plundered, several village leaders were abducted, and on the election day a terrorist attack claimed by Al-Qaeda killed nine people in central Mali (AL JAZEERA, 2020a). As a result, voter turnout was a little more than 12% in the capital Bamako (VOA, 2020). A second round of the parliamentary elections happened on April 19. As the war-torn country headed to a conclusion of years of wait to finally elect its members of parliament, violence still lurked around. At least 25 soldiers were killed in a terrorist attack in the town of Bamba, in the region of Gao, on April 6 (AL JAZEERA, 2020b). As the threat of violent actions increased, many people did not cast their ballots, and the Constitutional Court overrode the results in 31, which resulted in ten more seats for The Rally for Mali, the party led by the President IBK (AL JAZEERA, 2020d).

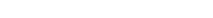

Naturally, revolt emerged from the situation. Mahmoud Dicko, a high-profile religious leader in the country, organized opposition parties to create the Mouvement du 5 juin - Rassemblement des forces patriotiques (in French) (June 5 Movement - Rally of Patriotic Forces) urging citizens to go out on the streets to protest on the 5th of June. As planned, thousands took the streets (AL JAZEERA, 2020c). The demonstrations eventually grew in power, and waves of protests spread around the country urging Keita to resign. At first, the movement was peaceful, however, on July 10 mass protests turned violent and at least 11 civilians were killed in clashes with security forces. Meanwhile, the President elaborated several proposals of reconciliation only to see them refused by the June 5 Movement. In addition, the Economic Community of West-African States sent a mission to the country to suggest several proposals of mediation, including the composition of the new government (AL JAZEERA, 2020c). All the attempts to negotiate failed, and the protests went on.

As the protests increased in size, the repression followed suit. On August 12, protesters were met with tear gas and water cannons at Bamako’s main square (AL JAZEERA, 2020d). The country, already ravaged by war, was taken by political instability. A few days later, on August 18, in the town of Kati, located in the outskirts of Bamako, soldiers began firing bullets into the air (REUTERS, 2020). Later, they stormed the capital arresting high-ranking government officials. The prime-minister Boubou Cissè attempted to negotiate with the insurgents, acknowledging they held legitimate frustrations (FRANCE 24, 2020a). However, his efforts had little success. After that, an insurgent leader claimed that both Keita and Cissè were being held captives at their residences (NY TIMES, 2020). The officials were later taken to the military camp in Kati, the starting point of the uprising (NY TIMES, 2020). As the news of the insurgence reached Bamako, thousands gathered at Bamako’s Independence Monument to demand the resignation of Keita (BBC, 2020).

IBK renounced at midnight of the same day, while the parliament and the government were dissolved (NY TIMES, 2020). Eventually, five military officers appeared on national television claiming to be the coup leaders. They were led by the colonel Assimi Goita and called themselves the National Committee for the Salvation of the People. In early September, the insurgents promised elections without specifying when they would happen (ALL AFRICA, 2020). Representatives of a myriad of countries and international organizations reprimanded the coup, and despite the call for elections within a year, the committee agreed to an 18-month transition to civilian rule (REUTERS, 2020). On the 25th of September, Bah Ndaw was inaugurated as the interim president, with Goita as his vice president, with both being military officers.

Analyzing the country’s indicators and its recent history, this year’s happenings did not seem unlikely even without the pandemic. However, the spread of COVID-19 has exacerbated its political instability. The country registered its first cases on the 25th of March after a few Malians returned from France (ITUC-AFRICA, 2020). Before the confirmation of the first cases, the country had already taken some safety measures, such as banning gatherings, closing schools, and suspending flights from nations with a high number of cases (ITUC-AFRICA, 2020). The number of infections did not increase dramatically and by mid-July was already in decline. Nevertheless, the impacts on the country were strong enough to harm a substantial portion of its population. The state of most Malians was already precarious, but with the pandemic poverty and living conditions have worsened considerably, food security followed suit, health security in general has deteriorated, and agriculture and farming have been severely hindered (THERA, 2020). The incapacity of the government to address these issues was a major source of unrest, being the motivation for many protesters to join the demonstrations.

Misinformation and discrimination were also a source of tension amidst the pandemic. The victims of the disease quite frequently were faced with stigmatization within their communities (FRANCE 24, 2020b). In addition, discriminatory attitudes towards new arrivals from displaced communities were common (HARO, 2020). Therefore, it is possible to assume that these aspects of the pandemic increased inter-community tension in Mali, helping to spread unrest and dissatisfaction in the country.

COVID-19 has also affected local peacebuilding initiatives. Since the announcement of restrictions, most organizations have suspended their field activities (THERA, 2020). Organizations such as the Association of Women Leadership and Sustainable Development (AFLED) played an important role in inter-community relations, and with their activities suspended, room for an escalation of tensions was created. These local actors have been a major source of education, health awareness, and information, and the halting of their actions added to the lack of internet access several sectors of the Malian society were left adrift, which has certainly contributed to the instability that has taken over the country in the past few months.

Putting everything together, it is evident that the pandemic has exacerbated the latest developments in Mali’s political scenario. The West-African country’s case is a good example to analyze how exogenous factors can influence outcomes in politics. Countries that do not have stable political institutions and have pre-existent social frictions are likely to face an increase in social tensions like Mali did.

Therefore, the Malian case is a hint of what might be around the corner for certain unstable regimes in Africa. The likes of DR Congo, Central African Republic, South Sudan, and so on, have faced long periods of instability, and may be suitable candidates to follow Mali’s path and face a regime change during the pandemic. Hence, it is important that NGOs and other actors involved in the structure of aid to these countries develop strategies to keep providing their services while restriction measures are upheld. In addition, international organizations who act in these countries must have for this kind of situation in order to avoid an escalation of tensions.

References:

AL JAZEERA. Dozens of Malian soldiers killed in attack on military base. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/4/7/dozens-of-malian-soldiers-killed-in-attack-on-military-base. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

AL JAZEERA. Mali crisis: From disputed election to president’s resignation. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/8/19/mali-crisis-from-disputed-election-to-presidents-resignation. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

AL JAZEERA. Mali police use tear gas to disperse anti-gov’t protesters. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/8/12/mali-police-use-tear-gas-to-disperse-anti-govt-protesters. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

AL JAZEERA. Malian parliamentary elections marred by kidnappings, attacks. Al Jazeera. Disponível em: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/3/31/malian-parliamentary-elections-marred-by-kidnappings-attacks. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

FRANCE 24. En Afrique subsaharienne, la stigmatisation est un frein dans la lutte contre coronavirus. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.france24.com/fr/20200520-en-afrique-subsaharienne-la-stigmatisation-est-un-frein-dans-la-lutte-contre-coronavirus. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

FRANCE 24. Mutinying soldiers detain Mali’s President Keita, Prime Minister Cisse. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.france24.com/en/20200818-ecowas-calls-on-mali-soldiers-to-end-the-mutiny. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

HARO, Juan. “Returning home isn’t an option”. UNICEF, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/niger-returning-home-isnt-option. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

ITUC-AFRICA. Mali’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. Disponível em: http://www.ituc-africa.org/Mali-s-response-to-the-COVID-19-pandemic.html. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

MACLEAN, Ruth. Mali’s President Exits After Being Arrested in Military Coup. The New York Times, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/18/world/africa/mali-mutiny-coup.html. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

REUTERS. Factbox: Why Mali is in turmoil again. 2020. Disponível em: https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-mali-politics-protests-factbox-idUKKCN25E1LA. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.

THERA, Boubacar. Mali’s security context exacerbated by COVID-19. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.peaceinsight.org/blog/2020/09/malis-security-context-exacerbated-covid-19/. Acesso em: 3 nov. 2020.