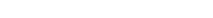

by Jales Caur

Thailand is classified as one of the three Buddhist countries in the contemporary world, following Hintington’s classification system (Machado, 2020a). Its millennial history is one of the most traditional and ancient in Asia – after the Chinese. The figure of a kingdom has not existed since the 1930s when the Kingdom of Siam was dissolved, and the constitutional monarchy country of Thailand was founded.

Since then, Thailand is one of the most visited countries in the world due to its old temples and cities, also for its marvellous beaches and natural diversity. However, the vision the country portrayed for the tourists is not the same as the real one, as Thailand is considered one of the most unequal countries in the entire world (Courtois & Beattie, 2020) – most of this caused by the democratic instability existent since the 2000s. And the current pandemic of COVID-19 aggravates the current struggles.

To understand Thailand, it is necessary to know Thai’s three main struggles: the political crisis since the 2000s, the economical struggles and the current pandemic scenario.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THAI’S DEMOCRACY

In 2005, protests arose against the then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, triggering a coup d’état in 2006. At this moment, society was divided into two: the yellow shirts, those who condemned the “parliamentary dictatorship'', and the red shirts, the other side composed of the elite, military, and the top-bureaucracy of Thailand. After a period of uncertainty about Thailand’s future amidst all the instability faced since 2006, another crisis disrupted in a new military coup in 2014 (Crisis Group, 2020).

Since then, Thailand had been ruled by the military junta known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) until 2019, when an election was held, allowing the generals to remain in power alleging a popular mandate. It is important to highlight the fact that NCPO had written a new constitution to Thailand, the one that created the current government’s framework. This constitution allowed them to indicate 250 of 500 members of the Senate, giving the military the advantage over the democratic process (Suhartono & Ramzy, 2019).

The election results were questioned by the Thai people considering all the irregularities and delays within the process. The junta’s premier, general Prayuth Chan-ocha, was rejected by most votes, but still took office after a change made in the formula of calculating party-lists seats only to gain a slight majority to allow it (Crisis Group, 2020). An associate professor of the Centre of Southeast Asian Studies of Kyoto University, Pavin Chachavalpongpun, in an interview for The New York Times (Suhartono & Ramzy, 2019), affirmed that the election was designed to maintain the power under military vigilance and prolong their rule over Thailand.

INEQUALITY AND ECONOMY WRECK AMIDST THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC

As previously mentioned, Thailand is one of the most unequal nations in the world. Think tanks, such as the Crisis Group (2020), point out that one of the main problems of Thailand is the usurpation of the economic apparatus of the state by the elite and its ruling according to their interests – bearing the necessity of a non-democratic environment for this to happen. And the Coronavirus pandemic only accentuated this phenomenon more.

It is forecasted that 11% of small businesses are in danger of closing permanently (Janssen, 2020), and most of them do not want to take on additional debt because of such a lack of confidence in the economic recovery – pointed as the main problem of Thailand (Parks, 2020). The GDP is predicted to contract within 8-10%, only recovering 4-5% in 2021, not being able to recover the pre-pandemic status until 2023 (Janssen, 2020). These numbers need to be considered aside with an optimist scenario when the tourism and the exportations return to their pre-Covid force.

Thailand became known as one of the best prepared countries in dealing with the Coronavirus pandemic, considering that the country registered the first case in January — being the second country in the world to confirm a positive infection —, with the government applying a complete lockdown achieving the mark of zero active cases within 44 days (Crisis Group, 2020). Nonetheless, this is pointed as the reason for the ongoing economic crisis – the worst since the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (Herald Reporters, 2020) and it was strengthened by the political stress caused by the rallies against the government.

Two-thirds of Thai labour pool’s income has declined by an average of approximately 50% (Reporters, 2020), and the Covid-19 crisis has increased the estimative of unemployment to 9,7 million according to the data of World Bank, a sizable concern considering the 69 million Thai inhabitants affected. These numbers reflect mostly on the tourism sector, responsible for approximately 6 million jobs and 18% of the GDP (Janssen, 2020). The hardest hit were Thai’s informal workers, counted as more than half of Thailand’s labour pool, with 81% of those in the tourism sector being unemployed in the middle of the pandemic (Parks, 2020).

Thailand’s opposition in government as well social groups are using the Prime Minister’s handlement of the pandemic against him, scrutinising the inefficacy of the emergency handout provided to the informal and laid-off workers – around $160 a month, 5000 baht at the local currency – that was abruptly ended after three months, leaving these people without any income (Parks, 200). This instability shows the malfunction of the current government to work for their people respecting their interests, highlighted as a necessity to remake the national constitution.

THAILAND: WHAT COMES NEXT?

Suggesting an institutional reform during the worst pandemic since 1918 to a developing country is the last recommended thing to do, even though some institutions and think tanks have pointed to it as a main solution of Thai’s problem. As mentioned, rallies are strong enough to disturb the economic system, affecting mainly the unemployed portion of society as well the owners of micro and small business. Based on Thai’s reality presented until now, Thai people can choose for the ousted of the current Prime Minister and call for new elections without the military.

However, dealing with military regimes is a synonym of expecting the use of hard force to maintain power, alleging the necessity of establishing the public order. This combat with such force during a pandemic scenario is not the best recommendation. It is also noticed the necessity of a national reform to improve the democracy index since, for example, in 2018, Thailand was responsible for decreasing the political liberty index among Buddhist countries (Machado, 2020b).

The Democracy Index, powered by The Economist (2019), now classifies Thailand in a zone of flawed democracy after an improvement that upgraded its status from hybrid democracy after the 2019 election. However, the data cannot fully translate the reality of a country, showing the necessity of humanising the data analysis because the situation in Thailand is not that democratic as the indexes report.

It is also important to mention the necessity of a new constitution that dialogues with the popular interests. In a fragile moment as the current one in Thailand – the pandemic and the governmental instability – adopting a bottom-up posture and considering the population’s wishes is the best path to run across while analysing this country. However, it is important to analyse previous experiences in developing countries. It can be assured that the Thai’s path is not going to be as simple as expected in the contemporary age, considering the prohibition of criticising the government in social media and mentioned use of force.

References

Courtois, L.; Beattie, T. (2020). Is Thailand heading for another political crisis? The Strategist. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/is-thailand-heading-for-another-political-crisis/

COVID-19 and a Possible Political Reckoning in Thailand. (2020). International Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/thailand/309-covid-19-and-possible-political-reckoning-thailand

Herald Reporters. (2020). Thailand Heads Toward Historic Recession Worse than 1997 Asian Crisis. Bangkok Herald. https://bangkokherald.com/business/economy/thailand-heads-toward-historic-recession-worse-than-1997-asian-crisis-utcc/

Janssen, P. (2020). Thailand’s Covid success turns economic failure. Asia Times. https://asiatimes.com/2020/08/thailands-covid-success-turns-economic-failure/

Machado, R. (2020a). As civilizações de Samuel Huntington – um exercício de ajustes e quantificação. Relações Exteriores. https://relacoesexteriores.com.br/as-civilizacoes-de-samuel-huntington-um-exercicio-de-ajustes-e-quantificacao/

Machado, R. (2020b, May 27). As Civilizações de Samuel Huntington. Webinar presented at the Congress of International Relations – CONRI. Brasilia, Brazil.

Parks, T. (2020). Thailand’s real crisis is the economy - Political grievances peripheral to economic damage being wrought by COVID-19. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Thailand-s-real-crisis-is-the-economy

Suhartono, M.; Ramzy, A. (2019). Thailand Election Results Signal Military’s Continued Grip on Power. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/09/world/asia/thailand-election-results.html

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2019). Democracy Index 2019: A year of democratic setbacks and popular protest.